The next July 1st, Croatia will become the twenty-eighth member of the EU. This has several consequences, not only on the Croatian society and the EU itself, but also on the rest of the Balkan region, and in particular on the neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina. About half a million Bosnian citizens, i.e. almost all of the Bosnian Croats, in fact, will become citizens of the Union, like their neighbors from Zagreb, Dalmatia or Slavonia. The boundary between “Europe” and the “Balkan world” will become more pronounced, and at the same time, more feeble.

The years that have marked the path of Croatia to independence and then to European integration have been accompanied by much rhetoric with de-historicising political trends as much as by cultural debates on the definition of both “Europe” of “the Balkans”, where the concepts of Balkanization of Europe and of Europeanization of the Balkans seem to offer the best food for thought.

In particular, the process is always the same, the collective identification in a self opposite to the other from himself. That is, the identification is based on the negation of the other. This process leads members of the same community to identify themselves not much on the basis of those shared values into it (be they national, religious or cultural), but rather on the basis of the foreignness of such values for the other. This trend, which is typical when processes of self-determination of peoples are in place, was a central part of the Balkan elites’ nationalist rhetoric of the 1990s. The main example is the one of the Croatian President Tudjman, who proclaimed the historical right of the Croatian nation to join the European Union as “the last bastion of Christian Europe”, in opposition to the Orientalism and Balkanism of those former neighbors become other.

And so the overused right to self-determination ends up consolidating identities, even invented, increasing differences in context that oppose the Croatian, Catholic and European, to the Serbian, Orthodox and Balkanic, as well as to the Bosnian, Muslim and Turkish.

With the accession of Croatia to the EU, those ethnically-Croatian citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina will be reserved the right to citizenship of the Union, with all the resulting benefits and convenience of the freedom of movement, including the capacity to work abroad and sustain their family in Bosnia with remittance monies.

The problem in all this is not that citizens of a third country find themselves from one day to another suddenly “in Europe”, but rather it lays in the reaffirmation of both those “boundaries of identity” that destabilize societies and states from within, and of the processes of construction of nation-states.

These two trends will have an impact on the peculiar Bosnian society and the sovereignty of its central state.

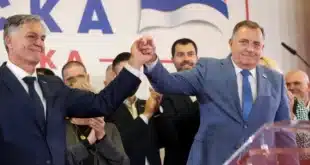

On the one hand, they will add a further “border”, a further other from itself, within the Croat-Muslim community, especially in the Federation, with the result that classmates and neighbors will have one more excuse with which to create social distinctions between: first-class citizens, allowed to travel without a passport, send remittances, and vote for the European Parliament, and second-class citizens linked to old problems such as inability to be employed and travel freely. And on the other hand, it will signal the final victory of those leaders, including Tuđman, who aspired to the creation of mono-ethnic nation-states, on the basis of historical national differences. To ensure this, the provisions of Dayton substantially recognize the right of citizenship of the “motherland” Croatia to the Bosnian Catholics (as of Serbia for the Orthodox ones), excluding the possibility of supranational identification within the central state.

In conclusion, we face the classic paradox of how the inclusion leads to the exclusion of the other, within the same community, and how identification is reduced to a mere “I know who I am because I know who I am not.”

Once again, the process of European integration leads to a de facto social disintegration. Once again, a united Europe has built walls, where it was trying to tear them down. Once again, it has consolidated the role of the nation-state rather than the one of civic states. Once again, Europe is back to divide Bosnia and Bosnia is divided thanks to Europe.

East Journal Quotidiano di politica internazionale

East Journal Quotidiano di politica internazionale