Articolo in italiano qui: BOSNIA: Verso il 2015. Un nuovo governo e una nuova prospettiva europea

No particular piece of news has come from Bosnia and Herzegovina in the last few years, if one excludes the floods and protest riots of 2014. The year 2015, however, might bring some positive surprises. With a new government in the making, and a new approach from the European Union, could Sarajevo be able to catch up with the other countries of the EU enlargement region?

Bosnia and Herzegovina, i.e., of stagnation?

The last two years have seen a peculiar dichotomy developing in Bosnia and Herzegovina. On the one hand, political reforms have stagnated, and a chronic economic crisis has left young people with the choice between unemployment, informal work, or emigration. On the other hand, civil society has awakened, calling for the respect of its civil (in the protests of bebolucija of the summer 2013) and social rights (in the street riots of February 2014), and citizens have rolled up their sleeves to repair the damages of the spring floods. While Mediterranean Europe was protesting against technocracy and for the return to the primacy of politics, in Dayton’s Bosnia the citizens were taking to the streets to demand a government of technocrats and experts, and the abolition of a part of the political class (identified in the intermediate level of government, the cantons) perceived as an integral part of the problem.

The elections of October 2014 did not seem to be harbingers of a particular change, despite the slogans of several parties calling for one. Yet some changes can be noticed. Western European newspapers have reported the news of a victory of the “nationalists”. In fact, most Bosnian parties today are conservative and identity-based parties rather than nationalist ones, often affiliated to the same EPP of Merkel and Tusk.

A new grand coalition for a new government

So, thanks to the change in the balance of power within the three political communities of the country, and despite details taking longer to be settled, the Bosnian parties announced only a month after the vote the profile of a new coalition government. Although the launch of the new Zvizdić executive came only in April, the situation did not result in a repetition of the impasse of 2010, when a parliamentary majority took fourteen months, over a year, to coagulate.

The government agreement brings together a great coalition of Bosniak parties (SDA, DF with the former opposition parties of the Bosnian Serbs (SDS, PDP, NDP), and with the Bosnian Croat party HDZ of Dragan Čović. The coalition, chaired by Denis Zvizdić, would thus reunite the heirs of the three nationalist parties that waged the 1992-1995 war with the last heirs of Tito’s socialism that in Bosnia maintains many supporters. These are nevertheless all transformed parties, which, two decades after, share the state framework of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the ultimate goal of accession to the European Union.

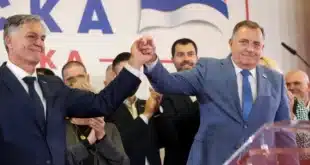

Once settled the issue of government formation, the main open question remains the relationship between the central government and the Republika Srpska (one of the two entities of the decentralized country), with Milorad Dodik’s SNSD party, in command of the latter, excluded from participation in the state executive. The relations between different levels of government in Bosnia are becoming more antagonistic (as shown by the SNSD threat to boycott the Parliament), right when the European Union requires Bosnian politicians to agree on a coordination mechanism between the different institutions entrusted with EU-related legal competences.

Towards a new European approach? Overcoming Sejdic and Finci

The European Union too appears ready to change gear with regard to Bosnia and Herzegovina, aided by the change of leadership in both Brussels (with the new Juncker Commission) and Sarajevo (with a new Head of Delegation and EU Special Representative, the Swedish diplomat Lars-Gunnar Wigemark).

The initiative was taken by UK and Germany, outgoing and incoming heavyweights of EU foreign policy towards the Balkans. In a joint letter to the leaders of the new EU Commission in early November, their foreign ministers Hammond and Steinmeier proposed a way out of the impasse that characterizes today’s European integration of Bosnia.

The country is still in the early stages of its path to EU membership. Its Constitution, signed at Dayton, reserves the highest offices (upper house and rotating Presidency) to the members of the three “constitutive peoples” (Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks). This is in contradiction with the norm of non-discrimination under the European Convention on Human Rights, as recognised in 2009 by the Strasbourg court in its Sejdić and Finci judgement.

The EU took over the issue as a precondition for the entry into force of the Stabilization and Association Agreement signed in 2008. This, however, soon turned into a ball and chain for the European course of the country. To be solved, it would require a complicated constitutional reform, for there is still no possibility of political agreement. And the reward expected by Bosnian politicians (the entry into force of a treaty whose main points, related to trade with the EU, are already covered by an interim agreement) is not enough to justify such an effort, thus undermining the mechanisms of operation of EU conditionality.

This issue was not overlooked in the debate between think tanks on the European approach to Bosnia. Within a year and a half, on the other hand, Brussels has radically changed its approach, moving from threatening not to recognize the results of the elections to focusing rather on socio-economic issues through the proposal of a “Pact for Growth“, in a move described by a senior diplomat as a Monty Python-style move: “and now for something completely different”.

The British/German initiative to boost the EU integration of Bosnia: a three-point plan

The British/German initiative aims to “broaden the agenda” to avoid “tackling intractable issues too early”, and to adapt the principle of conditionality to the specificities of Bosnia. The action plan, in three points, foresees the commitments required of Bosnian politicians and the respective EU rewards for compliance.

First, the new Bosnian leadership should undertake in writing to work on a plan for socio-economic and institutional reforms (including the Sejdić-Finci question) for the functionality of the state. The aim is to make Bosnia and Herzegovina, at the end of the process, ready to join the EU as a future member state. In return, the EU offers advice in drafting the reform agenda, and the long-delayed entry into force of the Stabilization and Association Agreement.

Second, with the approval and implementation of the first reforms, the EU could invite Bosnia and Herzegovina to apply for membership. Finally, with the implementation of the whole plan at an advanced stage (Sejdić-Finci included), the Commission could recommend that the EU Council open formal accession negotiations with the country. Hammond and Steinmeier remark that the plan does not entail a change in EU conditionality, but rather “a flexible and pragmatic approach to the sequencing of reforms”.

In fact, despite assurances to the contrary, the EU faces the issue of abandoning those preconditions that have proved politically untenable in the last five years, while saving face at the same time. The request for constitutional changes to solve the Sejdić-Finci issue is postponed to a later moment in EU-Bosnia relations – and it might not be the last postponement. Meanwhile, EU conditionality is recalibrated so that it can actually work out in Bosnia and Herzegovina too.

The opportunity of 2015: a relaunch for the European Integration of Bosnia?

The new head of EU diplomacy, Federica Mogherini, convened the EU Foreign Affairs Council on 17 November, but, busy with other dossiers (Libya, Ukraine), the EU foreign ministers gave only a general support to the initiative. The High Representative said that “there might be a chance to open a process on a new basis, without touching the conditionality of the enlargement process.” The caution would be due to the opposition of some member states (Belgium, Spain) to the relaxation of conditionality.

One thus had to wait for the European Council of 15 December 2014 to read the conclusions dedicated to Bosnia and Herzegovina, which incorporate the content of the British/German initiative, while stressing that it only entails a change in the sequence of the EU conditions, and not their content.

According to the Italian ambassador in Sarajevo, Ruggero Corrias, “No [reform] intends to threaten the Constitution, the Entities or the cantons. On the contrary, all point to a better functioning of the country and a more effective coordination between the State, Entities and cantons. All for the benefit of citizens and a more rapid approximation to the European standards.”

Now, the first months of 2015 will be crucial to see whether Bosnia and Herzegovina will be able to catch up with the other countries of the region. The tripartite presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina signed the “written commitment” to reforms on January 29, addressing it to the Bosnian Parliament, which approved it on February 23. The EU Council, thus, gave green light to the entry into force of the Association and Stabilisation Agreement.

Yet, several challenges remain open before this last step. They include updating the text of the association agreement as it had been negotiated one decade ago; negotiating a coordination mechanism among different administrative levels tasked with EU-related competences; the resumption of legislative activity, in a situation of political friction and different coalitions at state and entity level; and the lingering issue of a Constitutional reform in order to ensure Bosnia’s functionality for EU integration.

Should these manage to be addressed soon, and should the stabilization and association agreement finally enter into force, 2015 could see the resumption of relations between the EU and Bosnia, after too many years of stalemate.

East Journal Quotidiano di politica internazionale

East Journal Quotidiano di politica internazionale

Un commento

Pingback: BOSNIA: Verso il 2015. Un nuovo governo e una nuova prospettiva europea